Spare Rib

Spare Rib has been appearing monthly for over eight years: and in that time it has published and encouraged many women to develop their visual and verbal skills. The exhibition documents eight years of the women’s liberation movement. ‘We are fighting back against the images of women that surround and define us on advertising hoardings, in newspapers and conventional women’s magazines, in films and on television — not merely exposing the ways they are created, but also showing how we can begin to create our own.’

64 panels, 20″ x 30″. Made up largely of front covers.

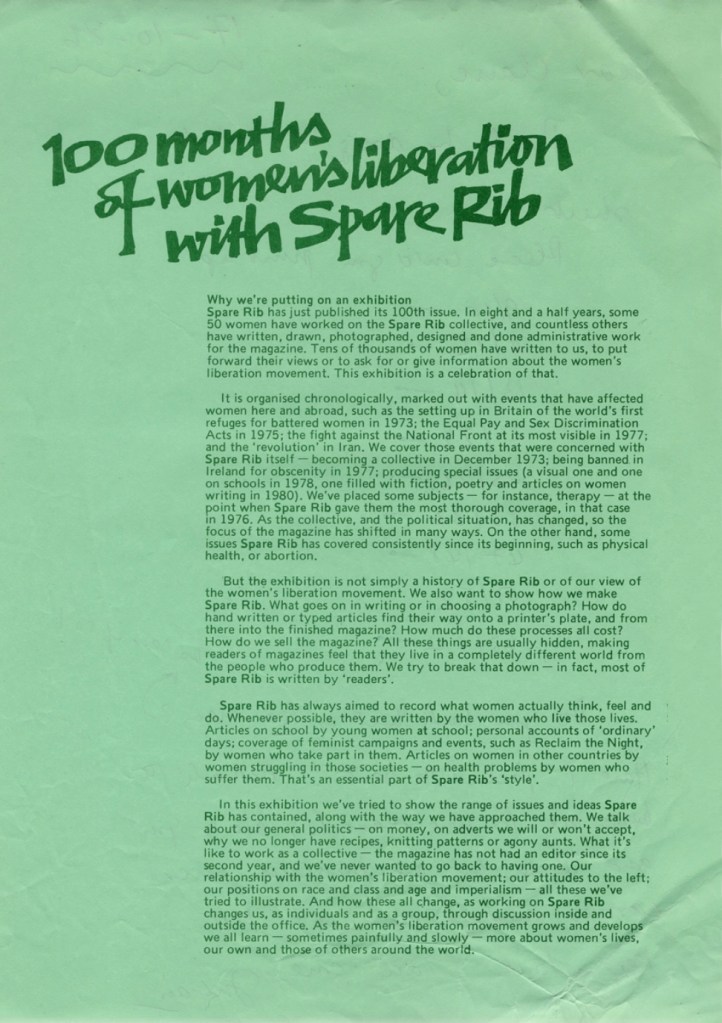

Why we’re putting on an exhibition

Spare Rib has just published its 100th issue. In eight and a half years, some 50 women have worked on the Spare Rib collective, and countless others have written, drawn, photographed, designed and done administrative work for the magazine. Tens of thousands of women have written to us, to put forward their views or to ask for or give information about the women’s liberation movement. This exhibition is a celebration of that.

It is organised chronologically, marked out with events that have affected women here and abroad, such as the setting up in Britain of the world’s first refuges for battered women in 1973; the Equal Pay and Sex Discrimination Acts in 1975; the fight against the National Front at its most visible in 1977; and the ‘revolution’ in Iran. We cover those events that were concerned with Spare Rib itself — becoming a collective in December 1973; being banned in Ireland for obscenity in 1977; producing special issues (a visual one and one on schools in 1978, one filled with fiction, poetry and articles on women writing in 1980). We’ve placed some subjects— for instance, therapy — at the point when Spare Rib gave them the most thorough coverage, in that case in 1976. As the collective, and the political situation, has changed, the focus of the magazine has shifted in many ways. On the other hand, some issues Spare Rib has covered consistently since its beginning, such as physical health, or abortion.

But the exhibition is not simply a history of Spare Rib or of our view of the women’s liberation movement. We also want to show how we make Spare Rib. What goes on in writing or in choosing a photograph? How do handwritten or typed articles find their way onto a printer’s plate, and from there into the finished magazine? How much do these processes all cost? How do we sell the magazine? All these things are usually hidden, making readers of magazines feel that they live in a completely different world from the people who produce them. We try to break that down — in fact, most of Spare Rib is written by ‘readers’.

Spare Rib has always aimed to record what women actually think, feel and do. Whenever possible, they are written by the women who live those lives. Articles on school by young women at school; personal accounts of ‘ordinary’ days; coverage of feminist campaigns and events, such as Reclaim the Night, by women who take part in them. Articles on women in other countries by women struggling in those societies — on health problems by women who suffer from them. That’s an essential part of Spare Rib’s ‘style’.

In this exhibition, we’ve tried to show the range of issues and ideas Spare Rib has contained, along with the way we have approached them. We talk about our general politics — on money, on adverts, we will or won’t accept, and why we no longer have recipes, knitting patterns or agony aunts. What it’s like to work as a collective — the magazine has not had an editor since its second year, and we’ve never wanted to go back to having one. Our relationship with the women’s liberation movement; our attitudes to the left; our positions on race and class and age and imperialism — all these we’ve tried to illustrate. And how these all change, as working on Spare Rib changes us, as individuals and as a group, through discussion inside and outside the office. As the women’s liberation movement grows and develops we all learn — sometimes painfully and slowly — more about women’s lives, our own and those of others around the world.